Running sp_helptext on the sys.system_internals_partition_columns system view reveals the following internal query:

SELECT

c.rsid AS partition_id,

c.rscolid AS partition_column_id,

c.rcmodified AS modified_count,

CASE c.maxinrowlen

WHEN 0 THEN p.length

ELSE c.maxinrowlen

END AS max_inrow_length,

CONVERT(BIT, c.status & 1) AS is_replicated, --RSC_REPLICATED

CONVERT(BIT, c.status & 4) AS is_logged_for_replication, --RSC_LOG_FOR_REPL

CONVERT(BIT, c.status & 2) AS is_dropped, --RSC_DROPPED

p.xtype AS system_type_id,

p.length AS max_length,

p.prec AS PRECISION,

p.scale AS scale,

CONVERT(sysname, CollationPropertyFromId(c.cid, 'name')) AS collation_name,

CONVERT(BIT, c.status & 32) AS is_filestream, --RSC_FILESTREAM

c.ordkey AS key_ordinal,

CONVERT(BIT, 1 - (c.status & 128)/128) AS is_nullable, -- RSC_NOTNULL

CONVERT(BIT, c.status & 8) AS is_descending_key, --RSC_DESC_KEY

CONVERT(BIT, c.status & 16) AS is_uniqueifier, --RSC_UNIQUIFIER

CONVERT(SMALLINT, CONVERT(BINARY(2), c.offset & 0xffff)) AS leaf_offset,

CONVERT(SMALLINT, SUBSTRING(CONVERT(BINARY(4), c.offset), 1, 2)) AS internal_offset,

CONVERT(TINYINT, c.bitpos & 0xff) AS leaf_bit_position,

CONVERT(TINYINT, c.bitpos/0x100) AS internal_bit_position,

CONVERT(SMALLINT, CONVERT(BINARY(2), c.nullbit & 0xffff)) AS leaf_null_bit,

CONVERT(SMALLINT, SUBSTRING(CONVERT(BINARY(4), c.nullbit), 1, 2)) AS internal_null_bit,

CONVERT(BIT, c.status & 64) AS is_anti_matter, --RSC_ANTIMATTER

CONVERT(UNIQUEIDENTIFIER, c.colguid) AS partition_column_guid,

sysconv(BIT, c.status & 0x00000100) AS is_sparse --RSC_SPARSE

FROM

sys.sysrscols c

OUTER APPLY

OPENROWSET(TABLE RSCPROP, c.ti) p

Nothing too out of the ordinary if you’ve looked at other internal queries. There’s a lot of bitmasking / shifting going on to extract multiple values from the same internal base table fields. One thing that is somewhat convoluted is the OPENROWSET(TABLE RSCPROP, c.ti) p OUTER APPLY being made.

A Google query for “sql server +rscprop” yields absolutely zilch results:

Simplifying the query to only show the fields using the fields referring the OPENROWSET (p) results, shows that the scale, precision, max_length, system_type_id and max_inrow_length are either extracted from the ti field value directly or indirectly:

SELECT

CASE c.maxinrowlen

WHEN 0 THEN p.length

ELSE c.maxinrowlen

END AS max_inrow_length,

p.xtype AS system_type_id,

p.length AS max_length,

p.prec AS PRECISION,

p.scale AS scale,

FROM

sys.sysrscols c

OUTER APPLY

OPENROWSET(TABLE RSCPROP, c.ti) p

To help me identifying the ti field structure, I’ve made a test table using a number of different column types:

CREATE TABLE TITest

(

A binary(50),

B char(10),

C datetime2(5),

D decimal(12, 5),

E float,

F int,

G numeric(11, 4),

H nvarchar(50),

I nvarchar(max),

J time(3),

K tinyint,

L varbinary(max),

M varchar(75),

N text

)

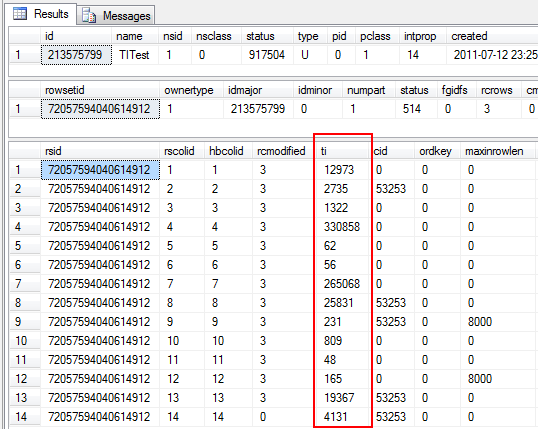

I’m not going to insert any data as that’s irrelevant for this purpose. For this next part, make sure you’re connected to the SQL Server using the Dedicated Administrator Connection. Now let’s query the sysrscols base table to see what values are stored in the ti field for the sample fields we’ve just created:

-- Get object id of TITest table

SELECT * FROM sys.sysschobjs WHERE name = 'TITest'

-- Get rowset id for TITest

SELECT * FROM sys.sysrowsets WHERE idmajor = 213575799

-- Get all columns for rowset

SELECT * FROM sys.sysrscols WHERE rsid = 72057594040614912

Besides the fact I’ve cut away some irrelevant columns, this is the result:

Note how we first get the object ID by querying sysschobjs, then the partition ID by querying sysrowsets and finally the partition columns by querying sysrscols. The marked ti column are the values from which we shall extract the scale, precision, max_length, system_type_id and max_inrow_length values.

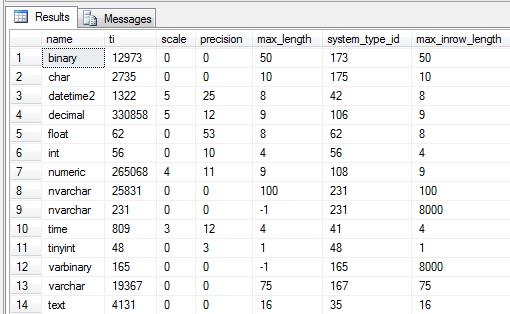

The following query will give a better row-by-row comparison between the ti value and the expected end result field values:

SELECT

t.name,

r.ti,

p.scale,

p.precision,

p.max_length,

p.system_type_id,

p.max_inrow_length

FROM

sys.system_internals_partition_columns p

INNER JOIN

sys.sysrscols r ON

r.rscolid = p.partition_column_id AND

r.rsid = p.partition_id

INNER JOIN

sys.types t ON

t.system_type_id = p.system_type_id AND

t.user_type_id = p.system_type_id

WHERE

partition_id = 72057594040614912

binary

Converting the first system_type_id into hex yields 0n173 = 0xAD. Converting the ti value yields 0n12973 = 0x32AD. An empirical test for all columns shows this to be true for them all. Thus we can conclude that the first byte (printed as the rightmost due to little endianness) stores the type. Extracting the value requires a simple bitmask operation:

12973 & 0x000000FF == 173

As for the length, the second byte stores the value 0x32 = 0n50. As the length is a smallint (we know it can be up to 8000, thus requiring at least a smallint), we can assume the next two bytes cover that. To extract that value, we’ll need a bitmask, as well as a shift operation to shift the two middlemost bytes one step to the right:

(12973 & 0x00FFFF00) >> 8 == 50

datetime2

This is the same for the char field. The datetime2 field is different as it stores the scale and precision values. 0n1322 in hex yields a value of 0x52A. 0x2A being the type (42). All that remains is the 0x5/0n5 which can only be the scale. A quick with a datetime(7) field yields the same result, though the precision is then 27. Thus I’ll conclude that for the datetime2 type, precision = 20 + scale. Extracting the scale from the second byte requires almost the same operation as before, just with a different bitmask:

(1322 & 0x0000FF00) >> 8 == 5

decimal

Moving onto decimal, we now have both a scale and a precision to take care of. Converting 0n330858 to hex yields a value of 0x50C6A. 0x6A being the type (106). 0x0C being the precision and finally 0x5 being the scale. Note that this is different from datetime2 – now the scale is stored as the third byte and not the second!

Extracting the third byte as the scale requires a similar bitmask & shift operation as previously:

(330858 & 0x00FF0000) >> 16 == 5

float

0n62 = 0x3E => the system_type_id value of 62. Thus the only value stored for the float is the type ID, the rest are a given. The same goes for the int, tinyint and similar fixed length field types.

numeric

0n265068 = 0x40B6C. 0x6C = the type ID of 108. 0xB = the precision value of 11. 0x4 = the scale value of 4.

nvarchar & nvarchar(max)

These are a bit special too. Looking at the first nvarchar(100) field we can convert 0n25832 to 0x64E7. 0xE7 being the type ID of 231. 0x64 being the length of 100, stored as a two byte smallint. This shows that the parsing of non-max (n)varchar fields is pretty much in line with the rest so far.

The nvarchar(max) differs in that it only stores the type ID, there’s no length. Given the lack of a length (technically the invalid length of 0 is stored), we read it as being –1, telling us that it’s a LOB/MAX field being stored with a max_length of –1 and a maximum in_row length of 8000, provided it’s not stored off-row.

Varbinary seems to follow the exact same format.

time

0n809 = 0x329. 0x29 = the type ID of 41. 0x3 being the scale of 3. As with the datetime2 field, the precision scales with the scale (pun only slightly intended) – precision = 9 + scale.

text

0n4131 = 0x1023. 0x23 = the type ID of 35. 0x10 being the max_length of 16. The reason the text type has a max_length of 16 is that text is a LOB type that will always be stored off row, leaving just a 16 byte pointer in the record where it’s logically stored.

Conclusion

The OPENROWSET(TABLE RSCPROP, x) obviously performs some dark magic. The ti field is an integer that’s used to store multiple values & formats, depending on the row type. Thus, to parse this properly, a switch would have to be made. Certain types also take values for a given – the precision fields based on the scale value, float having a fixed precision of 53 etc. It shouldn’t be long before I have a commit ready for OrcaMDF that’ll contain this parsing logic :)