At a recent TechTalk I talked about code access security and how to perform declarative and imperative security demands & requests. There’s no doubt declarative security checking is nicer than imperative checking, but not everything can be done declaratively.

Say we have the following method:

static void writeFile(string filePath)

{

File.WriteAllText("test", filePath);

}

We want to make sure we have permission to write to the filepath. Declaratively, we can request (SecurityAction.RequestMinimum) for an unrestricted FileIOPermission which would ensure that we had write access. But requesting unrestricted IO access is way overkill, since we only need access to select paths.

I got the question, why we could not perform that security check declaratively? As all declarative security checks are done at JIT and not at runtime, we simply do not have any knowledge of the filePath parameter value, and thus we can’t require permission for those specific paths. The only way we can demand permission for just the paths we need, is to do an imperative permission demand like so:

static void writeFile(string filePath)

{

var perm = new FileIOPermission(FileIOPermissionAccess.Write, filePath);

perm.Demand();

File.WriteAllText("test", filePath);

}

This however, clutters up our writeFile implementation as we now dedicate 2/3 lines for security checking… If only we could do this declaratively.

PostSharp Laos is a free open source AOP framework for .NET. Using PostSharp, we can define our own custom attributes that define proxy methods that will be invoked at runtime, instead of the actual method they decorate. Thus, we are able to define an imperative security check in our custom attribute, which will run before our actual method. I’ll jump right into it and present such an attribute:

// We need to make our attributes serializable:

// http://doc.postsharp.org/1.0/index.html#http://doc.postsharp.org/1.0/UserGuide/Laos/Lifetime.html

[Serializable]

public class FilePathPermissionAttribute : OnMethodInvocationAspect

{

private readonly string parameterName;

private readonly FileIOPermissionAccess permissionAccess;

private int parameterIndex = -1;

// In the constructor, we take in the required permission access (write, read, etc) as well as

// the parameter name that should be used for filepath input

public FilePathPermissionAttribute(FileIOPermissionAccess permissionAccess, string parameterName)

{

this.parameterName = parameterName;

this.permissionAccess = permissionAccess;

}

// This method is run at compiletime, and it's only run once - therefore performance is no issue.

// We use this to find the index of the requested parameter in the list of parameters.

public override void CompileTimeInitialize(MethodBase method)

{

ParameterInfo[] parameters = method.GetParameters();

for (int i = 0; i < parameters.Length; i++)

if (parameters[i].Name.Equals(parameterName, StringComparison.InvariantCulture))

parameterIndex = i;

if (parameterIndex == -1)

throw new Exception("Unknown parameter: " + parameterName);

}

// This method is run when our method is invoked, instead of our actual method. That means this method

// becomes a proxy for our real method implementation.

public override void OnInvocation(MethodInvocationEventArgs eventArgs)

{

// Demand the IOPermission to the requested file path

var perm = new FileIOPermission(permissionAccess, eventArgs.GetArgumentArray()[parameterIndex].ToString());

perm.Demand();

// If the permission demand above didn't explode, we are now free to invoke the real method.

// Calling .Proceed() automatically executes the real method, passing all parameters along.

eventArgs.Proceed();

}

}

In this attribute, we take two parameters, the FileIOPermissionAccess that is required, as well as the name of the parameter containing the file path we should demand permission for. The CompileTimeInitialize method is actually run at compile time - it will look through the list of parameters the method receives, and find the index of the parameter (by its name) and store it for later use. The stored values will be serialized in binary format, thus the need for making the class Serializable. If the parameter name is not found, we throw an exception. It’s important to note that this exception will be thrown at compile time, not at runtime. Thus there’s nothing dangerous in specyfying the parameter by its name (in string format) as we still have full compile time checking. Finally, the OnInvocation method is run when the decorated method is invoked. It’ll do the imperative security check and proceed with the original method call.

Using our FilePathPermission attribute, we can now rewrite our writeFile method as:

[FilePathPermission(FileIOPermissionAccess.Write, "filePath")]

static void writeFile(string filePath)

{

Console.WriteLine("Let's pretend we just successfully wrote a file to: " + filePath);

}

And there we go, we’ve now abstracted the security plumbing code out of our method implementation, while still doing an imperative security demand at runtime. In the same way, we can implement logging, exception handling, parameter sanitation, validation and so forth.

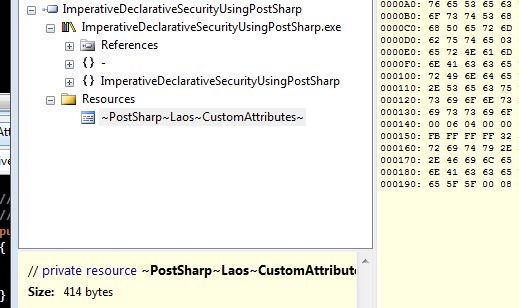

So what happens behind the scenes? The state we saved at compile time is embedded as a resource:

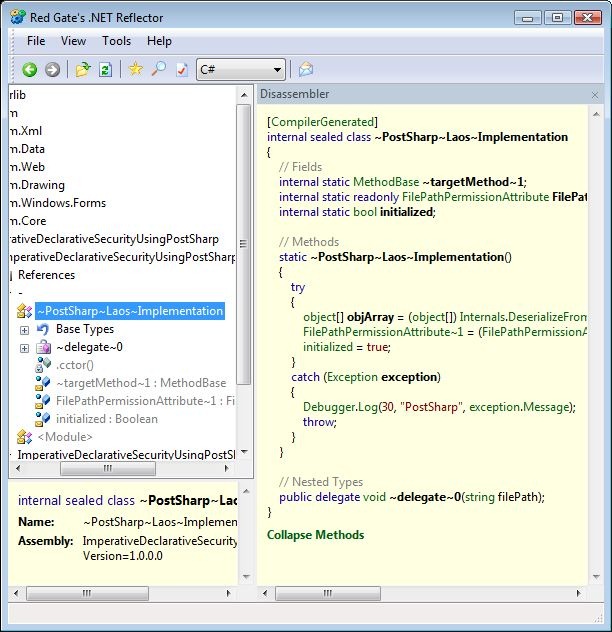

PostSharp also includes a special class it uses to keep track of the decorated methods, aspect state and so forth:

Let’s compare the complete initial code:

public class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

// This could be any kind of user input

string filePath = @"C:test.txt";

try

{

// We'll simulate that our assembly does not have FileIOPermission by denying it

var perm = new FileIOPermission(PermissionState.Unrestricted);

perm.Deny();

// Now let's simulate that we need to write a file to the user provided path

writeFile(filePath);

}

catch (SecurityException ex)

{

Console.WriteLine(ex);

}

finally

{

// Always, always, always remember to revert your stack walk modifiers

CodeAccessPermission.RevertDeny();

}

// So we keep the console window open

Console.Read();

}

[FilePathPermission(FileIOPermissionAccess.Write, "filePath")]

static void writeFile(string filePath)

{

Console.WriteLine("Let's pretend we just successfully wrote a file to: " + filePath);

}

}

With the reflected code after PostSharp has done its magic:

public class Program

{

// Methods

[CompilerGenerated]

static Program()

{

if (!~PostSharp~Laos~Implementation.initialized)

LaosNotInitializedException.Throw();

~PostSharp~Laos~Implementation.~targetMethod~1 = methodof(Program.writeFile);

~PostSharp~Laos~Implementation.FilePathPermissionAttribute~1.RuntimeInitialize(~PostSharp~Laos~Implementation.~targetMethod~1);

}

private static void ~writeFile(string filePath)

{

Console.WriteLine("Let's pretend we just successfully wrote a file to: " + filePath);

}

private static void Main(string[] args)

{

string filePath = @"C:test.txt";

try

{

try

{

FileIOPermission perm = new FileIOPermission(PermissionState.Unrestricted);

perm.Deny();

writeFile(filePath);

}

catch (SecurityException ex)

{

Console.WriteLine(ex);

}

}

finally

{

CodeAccessPermission.RevertDeny();

}

Console.Read();

}

[DebuggerNonUserCode, CompilerGenerated]

private static void writeFile(string filePath)

{

Delegate delegateInstance = new ~PostSharp~Laos~Implementation.~delegate~0(Program.~writeFile);

object[] arguments = new object[] { filePath };

MethodInvocationEventArgs eventArgs = new MethodInvocationEventArgs(delegateInstance, arguments);

~PostSharp~Laos~Implementation.FilePathPermissionAttribute~1.OnInvocation(eventArgs);

}

}

Note that these are debug builds, but the code modifications are the same in both release and debug mode. The main method is unaffected. A static initializer has been added which takes care of PostSharp’s intialization, obtaining pointers to the proxy methods - of which there is only one in this example. Finally, the writeFile method has been renamed to ~writeFile (otherwise unmodified), and a new writeFile method has been added. The new writeFile method, generated by PostSharp, invokes our FilePathPermissionAttributes OnInvocation method, passing in an MethodInvocationEventArgs parameter containing the parameter values.

While PostSharp does make a lot of things happen automagically at the compile stage, the effects are rather easy to get a comprehension of. Also, since PostSharp is completely open source and very well documented, you can always pinpoint exactly what happens and why it happens.

What about performance? There’s definitely a performance hit when using PostSharp. The build may be longer since PostSharp is invoked as part of the build process, but in my experience this is a rather quick process. As for runtime performance penalties, I constructed the following short app to test the performance hit by executing it both with and without the LaosTest attribute (using CodeProfiler for profiling):

[Serializable]

public class LaosTestAttribute : OnMethodInvocationAspect

{

public override void OnInvocation(MethodInvocationEventArgs eventArgs)

{

eventArgs.Proceed();

}

}

class Program

{

static int i = 0;

static void Main(string[] args)

{

TimeSpan ts = CodeProfiler.ProfileAction(() =>

{

for (int n = 0; n < 1000000; n++)

test();

}, 5);

Console.WriteLine(ts.ToString());

Console.Read();

}

[LaosTest]

static void test()

{

i++;

}

}

Profiling 10^6 calls to test() over five iterations yielded a total runtime of 13.879ms when using the PostSharp attribute - in release mode, excluding the first call. Running the same test, without the attribute, takes just 23ms. That’s 600 times quicker than when using PostSharp. But, still, that’s just 0.0027ms per call when using PostSharp (and nearly unmeasurable when not). Given that in all real life situations, the actual business logic will be much much slower, this performance penalty has almost no effect. Usually, we’re much better off sacrificing these minute amounts of speed over much better manageability of our source code.