Lately I’ve been working on nonclustered index parsing. One of my test cases proved to be somewhat more tricky than I’d anticipated, namely the parsing of nonclustered indexes for non-unique clustered tables. Working with non-unique clustered indexes, we’ll have to take care of uniquifiers when necessary.

The setup

Using an empty database I create the following schema and insert two rows. Note that the clustered index is created on the (ID, Name) columns and will thus have uniquifiers inserted since my rows aren’t unique. Also note that I’m intentionally creating a schema that will cause all three allocation unit types to be created – IN_ROW_DATA by default, LOB_DATA for the text column and finally ROW_OVERFLOW_DATA due to the overflowing varchar filler columns. This won’t serve any practical purpose besides being eye candy when looking at the data :)

-- Create schema

CREATE TABLE Test

(

ID int,

Name varchar(10),

FillerA varchar(8000) DEFAULT(REPLICATE('x', 5000)),

FillerB varchar(8000) DEFAULT(REPLICATE('y', 5000)),

Data text DEFAULT ('')

)

CREATE CLUSTERED INDEX CX_ID_Name ON Test (ID, Name)

CREATE NONCLUSTERED INDEX IX_ID ON Test (ID)

-- Insert dummy data

INSERT INTO

Test (ID, Name)

VALUES

(1, 'Mark'),

(1, 'Mark')

Verifying the presence of uniquifiers in the clustered index

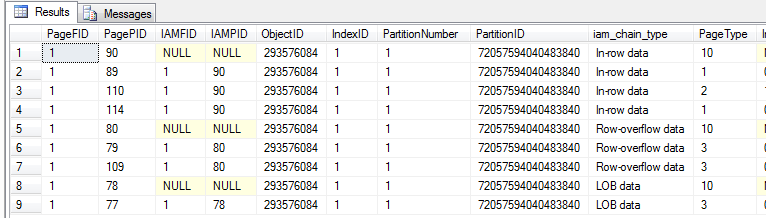

Running a quick DBCC IND on the Test table’s clustered index in the database (I’ve named mine ‘Y’ – I’m lazy), demonstrates the allocation of three allocation unit types as well as their tracking IAM pages.

DBCC IND (Y, 'Test', 1)

What we’re interested in are the two data pages of the clustered index – pages (1:89) and (1:114) in my case. Dumping the contents using dump style 3 shows that both have uniquifiers – one with a NULL value (interpreted as zero) and the other with a value of 1.

DBCC TRACEON (3604)

DBCC PAGE (Y, 1, 89, 3)

DBCC PAGE (Y, 1, 114, 3)

-- Page (1:89)

Slot 0 Column 0 Offset 0x0 Length 4 Length (physical) 0

UNIQUIFIER = 0

Slot 0 Column 1 Offset 0x4 Length 4 Length (physical) 4

ID = 1

Slot 0 Column 2 Offset 0x17 Length 4 Length (physical) 4

Name = Mark

<snip>

-- Page (1:114)

Slot 0 Column 0 Offset 0x17 Length 4 Length (physical) 4

UNIQUIFIER = 1

Slot 0 Column 1 Offset 0x4 Length 4 Length (physical) 4

ID = 1

Slot 0 Column 2 Offset 0x1b Length 4 Length (physical) 4

Name = Mark

<snip>

Notice how both are represented as slot 0 – this is because they stem from different pages, I’ve just cut out everything but the uniquifier column interpretation of the DBCC PAGE results. Also note how the first record doesn’t have any physical uniquifier value, while the second one uses 4 bytes. Finally make note that the uniquifier columns both reside at column ordinal 0.

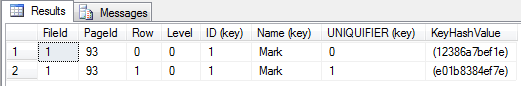

Comparing the uniquifiers in the nonclustered index

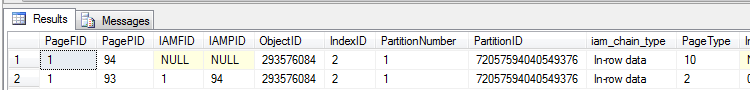

Now we’ll run DBCC IND to find the single index page for the nonclustered index – page (1:93) in my case (the uniquifier will only be present in the leaf level index pages – which is all we’ve got in this case).

DBCC IND (Y, 'Test', 2)

Dumping the contents of an index page using style 3 works differently for index pages – it returns a table resultset. It does confirm the presence of the uniquifier as well as our clustered index key columns (ID, Name) though:

DBCC PAGE (Y, 1, 93, 1)

Dumping in style 1 reveals the byte contents of the two rows, which is exactly what we need to locate the uniquifier:

DBCC PAGE (Y, 1, 93, 1)

Slot 0, Offset 0x60, Length 16, DumpStyle BYTE

Record Type = INDEX_RECORD Record Attributes = NULL_BITMAP VARIABLE_COLUMNS

Record Size = 16

Memory Dump @0x0000000009DEC060

0000000000000000: 36010000 00030000 01001000 4d61726b †6...........Mark

Slot 1, Offset 0x70, Length 22, DumpStyle BYTE

Record Type = INDEX_RECORD Record Attributes = NULL_BITMAP VARIABLE_COLUMNS

Record Size = 22

Memory Dump @0x0000000009DEC070

0000000000000000: 36010000 00030000 02001200 16004d61 †6.............Ma

0000000000000010: 726b0100 0000††††††††††††††††††††††††rk....

Notice how the second record is 6 bytes larger than the first. This is caused by the presence of the uniquifier on the second record. Since the uniquifier is stored as a 4 byte integer in the variable length section, we also need 2 extra bytes for storing the length of the uniquifier in the variable length column offset array – thus causing a total overhead of 6. The primary difference however, lies in the fact that the uniquifier is stored as the last variable length column in the nonclustered index (the 0100 0000 part of the second record), while in the clustered index data page it was stored as the first variable length column. This discrepancy is what caused me headaches when trying to parse both page types – I needed a way of determining what column ordinal the uniquifiers had for both the clustered and the nonclustered index.

Locating the uniquifier in a clustered index

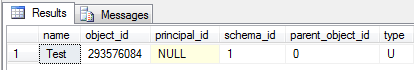

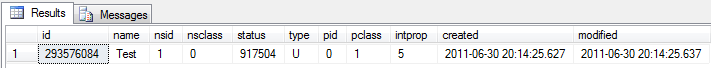

Thankfully there’s a plethora of DMVs to look in, it’s just a matter of finding the right ones. Let’s start out by querying sys.objects to get the object id of our table:

SELECT

*

FROM

sys.objects

WHERE

Name = 'Test'

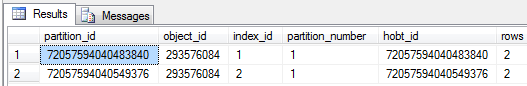

Armed with the object id, we can find the default partitions for our clustered and nonclustered indexes:

SELECT

*

FROM

sys.partitions

WHERE

object_id = 293576084

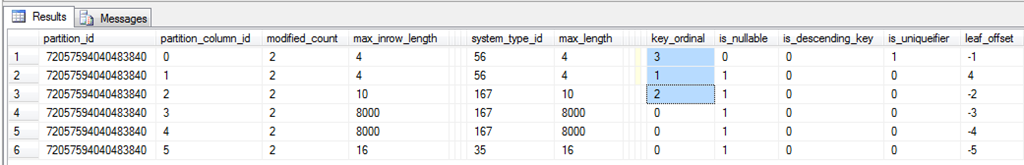

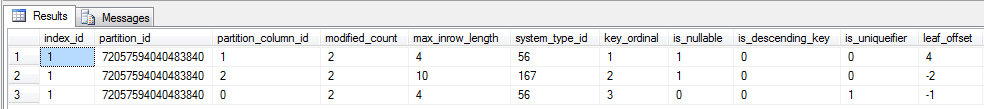

Armed with the partition id, we can find the partition columns for our clustered index (index_id = 1):

SELECT

*

FROM

sys.system_internals_partition_columns

WHERE

partition_id = 72057594040483840

Now would you take a look at that marvelous is_uniquifier column (we’ll ignore the alternative spelling for now). Using this output we can see that the first row is the uniquifier – being the third part of our clustered key (key_ordinal = 3). The leaf_offset column specifies the physical order in the record, fixed length columns being positive and variable length columns being negative. This confirms what we saw earlier, that the uniquifier is the first variable length column stored, with the remaining columns coming in at leaf offset –2, –3, –4 and –5.

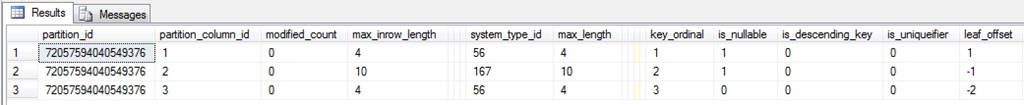

Locating the uniquifier in a nonclustered index

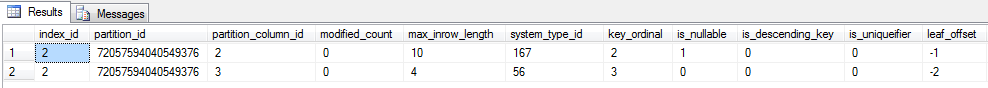

Well that was easy, let’s just repeat that using the partition id of our nonclustered index (index_id = 2):

SELECT

*

FROM

sys.system_internals_partition_columns

WHERE

partition_id = 72057594040549376

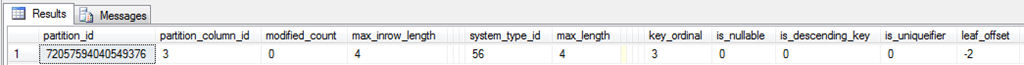

But what’s this, curses! For nonclustered indexes, the is_uniquifier column is not set, even though we can see there are three columns in our nonclustered index (the explicitly included ID, the implicitly included Name column that’s part of the clustered index key as well as the uniquifier which is also part of the clustered index key). So now we know that the uniquifier is shown in the result set, we just can’t trust the is_uniquifier column. However – to the best of my knowledge no other integer columns are stored as a variable length column, besides the uniquifier. Thus, we can add a predicate to the query returning just integers (system_type_id = 56) with negative leaf_offsets:

SELECT

*

FROM

sys.system_internals_partition_columns

WHERE

partition_id = 72057594040549376 AND

system_type_id = 56 AND

leaf_offset < 0

And that’s it, we now have the uniquifier column offset in the variable length part of our nonclustered index record!

The pessimistic approach

As I can’t find any info guaranteeing that the uniquifier is the only integer stored in the variable length part of a record, I came up with a secondary way of finding the uniquifier column offset. This method is way more cumbersome though and I won’t go into complete details. We’ll start out by retrieving all columns in the nonclustered index that are not explicitly part of the nonclustered index itself (by removing all rows present in sys.index_columns for the index):

DECLARE @TableName sysname = 'Test'

DECLARE @NonclusteredIndexName sysname = 'IX_ID'

SELECT

i.index_id,

pc.*

FROM

sys.objects o

INNER JOIN

sys.indexes i ON i.object_id = o.object_id

INNER JOIN

sys.partitions p ON p.object_id = o.object_id AND p.index_id = i.index_id

INNER JOIN

sys.system_internals_partition_columns pc on pc.partition_id = p.partition_id

WHERE

o.name = @TableName AND

i.name = @NonclusteredIndexName AND

NOT EXISTS (SELECT * FROM sys.index_columns WHERE object_id = o.object_id AND index_id = i.index_id AND key_ordinal = pc.key_ordinal)

These are the remaining columns that are stored as the physical part of the index record. Given that they’re not part of the index definition itself, these are the columns that make up the remainder of the clustered key – the Name and Unuiquifier columns in this example.

Now we can perform the same query for the clustered index, though this time only filtering away those that are not part of the key itself (that is, key_ordinal > 0):

DECLARE @TableName sysname = 'Test'

DECLARE @NonclusteredIndexName sysname = 'CX_ID_Name'

SELECT

i.index_id,

pc.*

FROM

sys.objects o

INNER JOIN

sys.indexes i ON i.object_id = o.object_id

INNER JOIN

sys.partitions p ON p.object_id = o.object_id AND p.index_id = i.index_id

INNER JOIN

sys.system_internals_partition_columns pc on pc.partition_id = p.partition_id

WHERE

o.name = @TableName AND

i.name = @NonclusteredIndexName AND

key_ordinal > 0

ORDER BY

key_ordinal

At this point we can compare these two result sets from the highest key_ordinal and downwards. Basically we just need to find the first match between the uniquifier column in the clustered index output and the assumed uniquifier column in the nonclustered index output. Until my assumption of the uniquifier being the only variable length integer, I wouldn’t recommend using this method though.

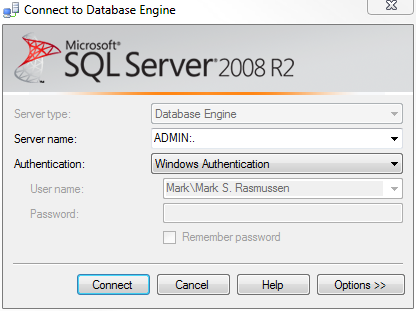

The hardcore approach – using base tables

All those DMV’s certainly are nifty, but I just can’t help but feel I’m cheating. Let’s try and redo the optimistic (uniquifier being the only variable length integer) approach without using DMVs. Start out by connecting to your database using the dedicated administrator connection, this will allow you to query the base tables:

We’ll start out by querying sys.sysschobjs, which is basically the underlying table for sys.objects:

SELECT

*

FROM

sys.sysschobjs

WHERE

name = 'Test'

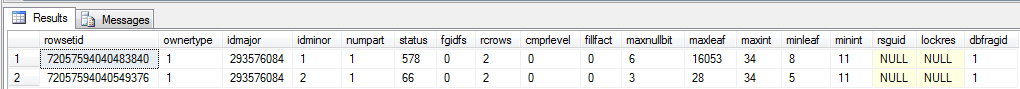

Now we’ll query sys.sysrowsets, which is basically the underlying table for sys.partitions. In the base tables, idmajor is the column name we commonly know as object_id and idminor is what we’d usually know as index_id:

SELECT

*

FROM

sys.sysrowsets

WHERE

idmajor = 293576084

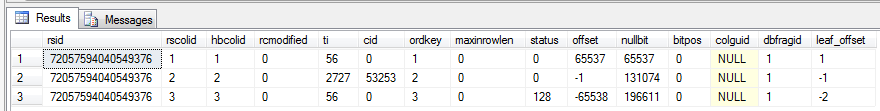

Checking out the row with idminor = 2, we’ve now got the rowsetid (partition id) of our nonclustered index. Now we just need to find the columns for the index – and that’s just what sys.sysrscols is for, the base table behind sys.system_internals_partition_columns:

SELECT

*,

CAST(CAST(offset & 0xFFFF AS binary(2)) AS smallint) AS leaf_offset

FROM

sys.sysrscols

WHERE

rsid = 72057594040549376

Note that the leaf_offset column isn’t persisted as an easily read value – it’s actually stored as an integer in the offset column. The offset column stores not only the value for the leaf_offset column but also for the internal_offset column – we just have to do some masking and conversion to get it out.

The following query helps to show exactly what we’re doing to extract the leaf_offset value from the offset column value:

SELECT

offset,

CAST(CAST(offset & 0xFFFF AS binary(2)) AS smallint) AS leaf_offset,

CAST(offset AS binary(4)) AS HexValue,

CAST(offset & 0xFFFF AS binary(4)) AS MaskedHexValue,

CAST(offset & 0xFFFF AS binary(2)) AS ShortenedMaskedHexValue

FROM

sys.sysrscols

WHERE

rsid = 72057594040549376

The HexValue shows the offset column value represented in hex – no magic yet. After applying the 0xFFFF bitmask (0b1111111111111111 in binary), only the first 16 bits / 2 (starting from the right since we’re little endian) bytes will keep their value. Converting to binary(2) simply discards the last two bytes (the 0x0000 part).

0x0001 is easily converted to the decimal value 1. 0xFFFF and 0xFFFE correspond to the decimal values 65.535 and 65.534 respectively. The way storing smallints work, 0 is stored as 0x0, 32.767 is stored as 0x7FFF and from there on the decimal value rolls over into –32.768 with a hex value of 0x8000 – continuing all the way up the –1 = 0xFFFF. And that’s why we can convert the binary(2) representations of the offset columns into the –1 and –2 decimal values.