Deadlocks in any database can be a hard beast to weed out, especially since they may hide latently in your code, awaiting that specific moment when they explode. An API website, exposing a series of webservices, had been working fine for months, until I decided to run my client app with a lot more threads than usual.

Great. So we have a deadlock, what’s the first step in fixing it? I’ve outlined the code in PaperHandler.cs that caused the issue, though in pseudo code format:

using (var ts = new TransactionScope())

{

if ((SELECT COUNT(*) FROM tblPapers WHERE Url = 'newurl') > 0)

throw new UrlNotUniqueException();

// ... Further validation checks

INSERT INTO tblPapers ... // This is where the deadlock occurred

}

To see how the above code may result in a deadlock, let’s test it out in SQL Server Management Studio (SSMS). Open a new query and execute the following, to create the test database & schema:

-- Create new test database - change name if necessary

CREATE DATABASE Test

GO

USE Test

-- Create the test table

CREATE TABLE tblPapers

(

ID int identity(1,1) NOT NULL,

Url nvarchar(128) NOT NULL

)

-- Make the ID column a primary clustered key

ALTER TABLE dbo.tblPapers ADD CONSTRAINT PK_tblPapers PRIMARY KEY CLUSTERED

(

ID ASC

)

ON [PRIMARY]

-- Add a nonclustered unique index on the Url column to ensure uniqueness

CREATE UNIQUE NONCLUSTERED INDEX NC_Url ON tblPapers

(

Url ASC

)

ON [PRIMARY]

The tblPapers table contains a number of entities, and each of them must have a unique Url value. Therefore, before we insert a new row into tblPapers, we need to ensure that it’s going to be unique.

Now open two new query windows and insert the following query text into both of them:

USE Test

SET TRANSACTION ISOLATION LEVEL SERIALIZABLE

BEGIN TRAN

-- Ensure unique URL

DECLARE @NewUrl varchar(128); SET @NewUrl = 'newurl'

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM tblPapers WHERE Url = @NewUrl

-- Insert row if above query returned 0 <=> URL is unique

DECLARE @NewUrl varchar(128); SET @NewUrl = 'newurl'

INSERT INTO tblPapers (Url) VALUES (@NewUrl)

In SQL Server 2005/2008, READ COMMITTED is the default transaction level - we’re being explicit about using the SERIALIZABLE isolation level, however. The reason we’re going to use the SERIALIZABLE isolation mode is that while READ COMMITTED is the default mode in SQL Server, whenever you create an implicit transaction using TransactionScope, it’s using the SERIALIZABLE isolation mode by default!

Now, observe what happens if you run two queries concurrently in the following order:

Query A

USE Test

SET TRANSACTION ISOLATION LEVEL SERIALIZABLE

BEGIN TRAN

Query B

USE Test

SET TRANSACTION ISOLATION LEVEL SERIALIZABLE

BEGIN TRAN

Query A

-- Ensure unique URL

DECLARE @NewUrl varchar(128); SET @NewUrl = 'newurl'

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM tblPapers WHERE Url = @NewUrl

Query B

-- Ensure unique URL

DECLARE @NewUrl varchar(128); SET @NewUrl = 'newurl'

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM tblPapers WHERE Url = @NewUrl

Query A

-- Insert row since URL is unique

DECLARE @NewUrl varchar(128); SET @NewUrl = 'newurl'

INSERT INTO tblPapers (Url) VALUES (@NewUrl)

Query B

-- Insert row since URL is unique

DECLARE @NewUrl varchar(128); SET @NewUrl = 'newurl'

INSERT INTO tblPapers (Url) VALUES (@NewUrl)

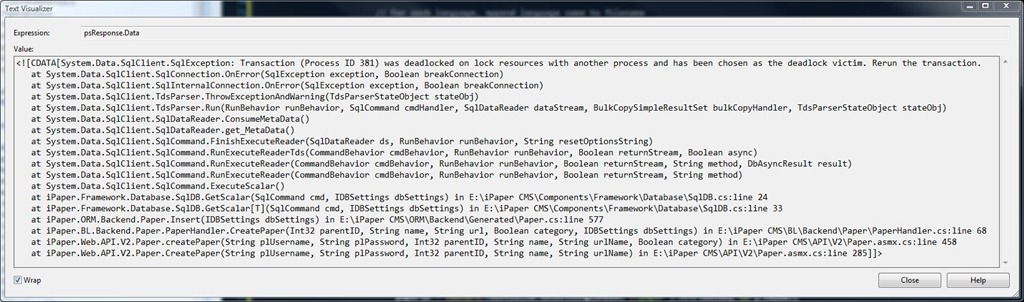

After executing the last query, you should get the following error in one of the windows:

Msg 1205, Level 13, State 47, Line 4

Transaction (Process ID 53) was deadlocked on lock resources with another process and has been chosen as the deadlock victim. Rerun the transaction.

While in the second window, you’ll notice that the insertion went through:

(1 row(s) affected)

What happened here is that the two transactions get locked up in a deadlock. That is, neither one of them could continue without one of them giving up, as they were both waiting on a resource the other transaction had locked.

But what happened, how did this go wrong? Isn’t the usual trick to make sure you perform actions in the same order, and you’ll avoid deadlocks? Unfortunately it’s not that simple, your isolation level plays a large part as well. In this case we know which queries caused the deadlock, but we could’ve gotten the same information using the profiler. Perform a rollback of the non-victimized transaction so the tblPapers table remains unaffected.

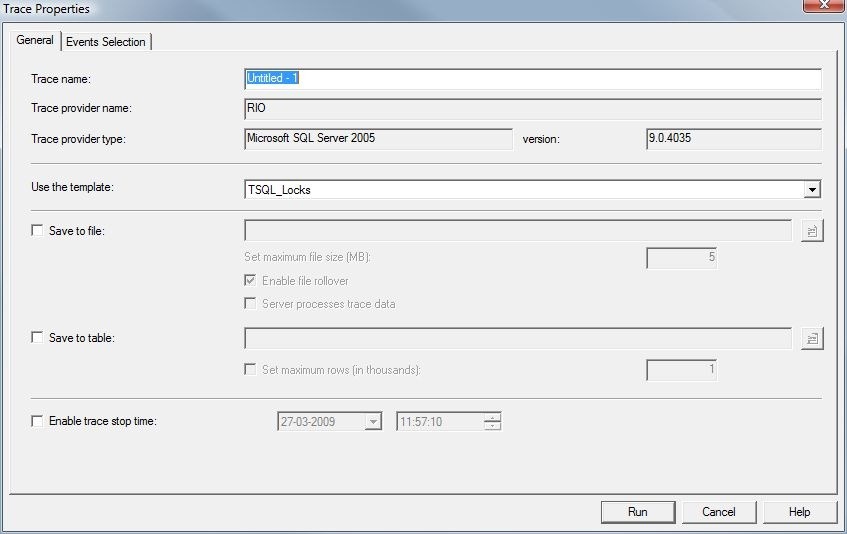

Startup the profiler and connect to the database server. Choose the TSQL_Locks template:

Make sure only the relevant events are chosen, to limit the amount of data we’ll be presented with. If necessary, put extra filters on the database name so we avoid queries from other databases. You can also filter it on the connection ID’s from SSMS if necessary:

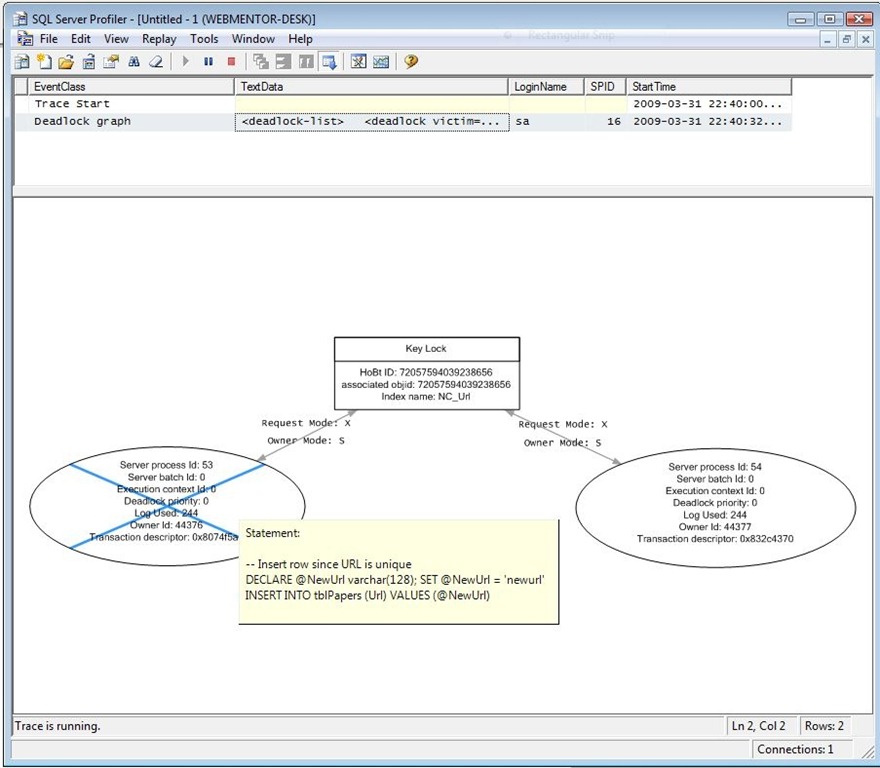

If we run the profiler in the background while executing all steps in SSMS in the meantime, we’ll notice a an important event in the profiler, the Deadlock graph. If we hover the mouse over either of the circles representing the two individual processes, we’ll get a tooltip showing the exact query that was run when the deadlock occurred - the two insert queries:

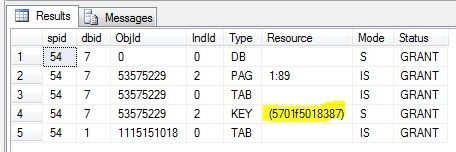

Ok, so now that we know what step caused the deadlock, the question now is, why did it occur? Perform a rollback of the non-victimized transaction. Now run step 1-3 again, and run the following query in window A:

sp_lock @@SPID

The result should resemble this (ID’s will be different):

Notice the highlighted object ID. Now right click on the deadlock graph in the profiler results table and select “Extract event data”. Save the file somewhere and open it in Visual Studio (as XML).

You’ll notice the following two lines:

<process id="process383a5c8" ... waitresource="KEY: 7:72057594039238656 (5701f5018387)" ... />

<process id="process383a868" ... waitresource="KEY: 7:72057594039238656 (5701f5018387)" ... />

What these lines tells us is that both processes are waiting on the same resource, namely 5701f5018387. Looking at our sp_locks result from before, we can see that that particular resource has a shared lock (S) on it.

And this brings us down to the core issue - the SERIALIZABLE isolation mode. Different isolation modes provide different locking levels, serializable being one of the more pessimistic ones. SERIALIZABLE will:

- Request shared locks on all read data (and keep them until the transaction ends), preventing non-repeatable reads as other transactions can’t modify data we’ve read.

- Prevent phantom reads - that is, a SELECT query will return the same result even if run multiple times - other transactions can’t insert data while we’ve locked it. SQL Server accomplishes this by either locking at the table or key-range level.

If we look at the Lock Compatibility chart.aspx), we’ll see that “Shared (S)” locks are compatible with other S & IS (Intent Shared) locks. This means both of the processes are able to perform a shared lock on the initial SELECT COUNT(*) key range. When the INSERT statement is then performed, the database will then attempt to get an exclusive (X) lock on the data - but since the other process has a shared lock, we’ll have to wait for it to be released. When the second process tries to perform an INSERT as well, it’ll try to get an exclusive lock on the same data. At this point we have two processes that both have a shared lock on the same piece of data, and they both want an exclusive lock on the data. The only way to get out of this situation is to dedicate one of the transactions as a victim and perform a rollback. The unaffected process will perform the INSERT and will be able to commit.

How do we then get rid of the deadlock situation? We could change the isolation mode to the default READ COMMITTED like so:

var tsOptions = new TransactionOptions();

tsOptions.IsolationLevel = IsolationLevel.ReadCommitted;

using (var ts = new TransactionScope(TransactionScopeOption.Required, tsOptions))

{

...

ts.Complete();

}

However, that will result in another problem if we run the same steps as before:

Msg 2601, Level 14, State 1, Line 3

Cannot insert duplicate key row in object 'dbo.tblPapers' with unique index 'NC_Url'.

The statement has been terminated.

As READ COMMITTED does not protect us against phantom reads, it won’t take shared locks on read data. Thus the second process is able to perform the insert without us knowing (we still think COUNT(*) is = 0). As a result, we’ll fail by violating the unique NC_Url index constraint.

What we’re looking for is an even more pessimistic isolation level - we not only need to protect ourselves against phantom reads, we need to protect against locks on the same data as we’ve read (we don’t care if someone reads our data using READ UNCOMMITTED, that’s their problem - as long as they don’t lock our data). However, SERILIZABLE is the most pessimistic isolation level in SQL Server, so we’re outta luck. That is… Unless we use a locking hint.

Locking hints tell the database engine what kind of locking we would like to use. Take note that locking hints are purely hints - they’re not orders. In this case however, SQL Server does obey our command. What we need is the UPDLOCK hint. Change the query so it includes an UPDLOCK hint in the first SELECT statement:

-- Ensure unique URL

DECLARE @NewUrl varchar(128); SET @NewUrl = 'newurl'

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM tblPapers (UPDLOCK) WHERE Url = @NewUrl

The UPDLOCK hint tells SQL Server to acquire an update lock on the key/range that we’ve selected. Since shared locks and update locks are not compatible, the second process will have to wait until the first transaction either commits or performs a rollback. The second process won’t return the result of the first SELECT COUNT(*) query until the first process is done - or a timeout occurs.

Note that while this method protects us against the deadlocks & constraint violations, it does so at the cost of decreased concurrency. This will result in other operations being blocked until the insertion procedure is done. In my case, this is a rather rare procedure, so it does not matter. One way to alleviate this problem would be to use the READ COMMITTED SNAPSHOT isolation level in other parts of the application where it’s applicable. YMMV!