I recently had a look at the statistics storage of a system I designed some time ago. As is usually the case, back when I made it, I neither expected nor planned for a large amount data, and yet somehow that table currently has about 750m rows in it.

The basic schema for the table references a given entity and a page number, both represented by ints. Furthermore we register the users Flash version, their IP and the date of the hit.

CREATE TABLE #HitsV1

(

EntityID int NOT NULL,

PageNumber int NOT NULL,

Created datetime NOT NULL,

FlashVersion int NULL,

IP varchar(15) NULL

)

Taking a look at the schema, we can calculate the size of the data in the record (synonymous to a row, indicating the structure on disk) to be 4 + 4 + 8 + 4 + 15 = 35 bytes. However, there’s overhead to a record as well, and the narrower the row, the more overhead, relatively.

In this case, the overhead consists of:

| Bytes | Content |

|---|---|

| 2 | Status bits A & B |

| 2 | Length of fixed-length data |

| 2 | Number of columns |

| 1 | NULL bitmap |

| 2 | Number of variable length columns |

| 2 | Variable length column offset array |

Finally, each record has an accompanying two byte pointer in the row offset array, meaning the total overhead per record amounts to 13 bytes. Thus we’ve got 48 bytes in total per record, and with 8096 bytes of available data space per page, that amounts to a max of about 168 rows per page.

To test things out, we’ll insert 100k rows into the table:

BEGIN TRAN

DECLARE @Cnt int = 0

WHILE @Cnt < 100000 BEGIN

INSERT INTO #HitsV1 VALUES (1, 1, getdate(), 1, '255.255.255.255')

SET @Cnt = @Cnt + 1

END

COMMIT

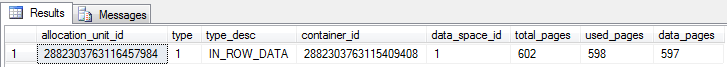

Note that the actual values doesn’t matter as we’re only looking at the storage effects. Given 168 rows per page, 100.000 rows should fit in about 100.000 / 168 ~= 596 pages. Taking a look at the currently used page count, it’s a pretty close estimate:

SELECT

AU.*

FROM

sys.allocation_units AU

INNER JOIN

sys.partitions P ON AU.container_id = P.partition_id

INNER JOIN

sys.objects O ON O.object_id = P.object_id

WHERE

O.name LIKE '#HitsV1%'

Reconsidering data types by looking at reality and business specs?

If we start out by looking at the overhead, we’ve got a total of four bytes spent on managing the single variable-length IP field. We could change it into a char(15), but then we’d waste space for IP’s like 127.0.0.1 and there’s the whole spaces-at-the-end issue. If we instead convert the IP into an 8-byte bigint on the application side, we save 7 bytes on the column itself, plus 4 for the overhead!

Looking at the FlashVersion field, why do we need a 4-byte integer capable of storing values between –2.147.483.468 and 2.147.483.647 when the actual Flash version range between 1 and 11? Changing that field into a tinyint just saved us 3 bytes more per record!

Reading through our product specs I realize we’ll never need to support more than 1000 pages per entity, and we don’t need to store statistics more precisely than to-the-hour. Converting PageNumber to a smallint just saved 2 extra bytes per record!

As for the Created field, it currently takes up 8 bytes per record and has the ability to store the time with a precision down to one thee-hundredth of a second – obviously way more precise than what we need. Smalldatetime would be much more fitting, storing the precision down to the minute and taking up only 4 bytes – saving a final 4 bytes per record. I we wanted to push it to the extreme we could split Created into two fields – a 3 byte date field and a 1 byte tinyint field for the hour. Though it’d take up the same space, we just gained the ability to store dates all the way up to year 9999 instead of only 2079. As the rapture is coming up shortly, we’ll skip that for now.

So to sum it up, we just saved:

| Bytes | Cause |

|---|---|

| 11 | Converting IP to bigint |

| 3 | Converting FlashVersion to tinyint |

| 2 | Converting PageNumber to smallint |

| 4 | Converting Created to smalldatetime |

In total, 20 bytes per record, resulting in a new total record size of 26 – 28 including the slot offset array pointer. This means we can now fit in 289 rows per page instead of the previous 168.

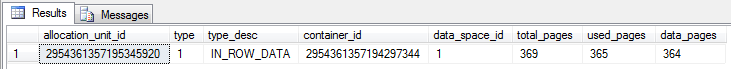

Testing the new format reveals we’re down to just 364 pages now:

CREATE TABLE #HitsV2

(

EntityID int NOT NULL,

CategoryID smallint NOT NULL,

Created smalldatetime NOT NULL,

FlashVersion tinyint NULL,

IP bigint NULL

)

BEGIN TRAN

DECLARE @Cnt int = 0

WHILE @Cnt < 100000 BEGIN

INSERT INTO #HitsV2 VALUES (1, 1, getdate(), 1, 1)

SET @Cnt = @Cnt + 1

END

COMMIT

SELECT

AU.*

FROM

sys.allocation_units AU

INNER JOIN

sys.partitions P ON AU.container_id = P.partition_id

INNER JOIN

sys.objects O ON O.object_id = P.object_id

WHERE

O.name LIKE '#HitsV2%'

The more rows, the more waste

Looking back at the 750m table, the original format would (assuming an utopian zero fragmentation) take up just about:

750.000.000 / 168 * 8 / 1024 / 1024 ~= 34 gigabytes.

Whereas the new format takes up a somewhat lower:

750.000.000 / 289 * 8 / 1024 / 1024 ~= 20 gigabytes.

And there we have it – spending just a short while longer considering the actual business & data needs when designing your tables can save you some considerable space, resulting in better performance and lower IO subsystem requirements.